7 July 2020

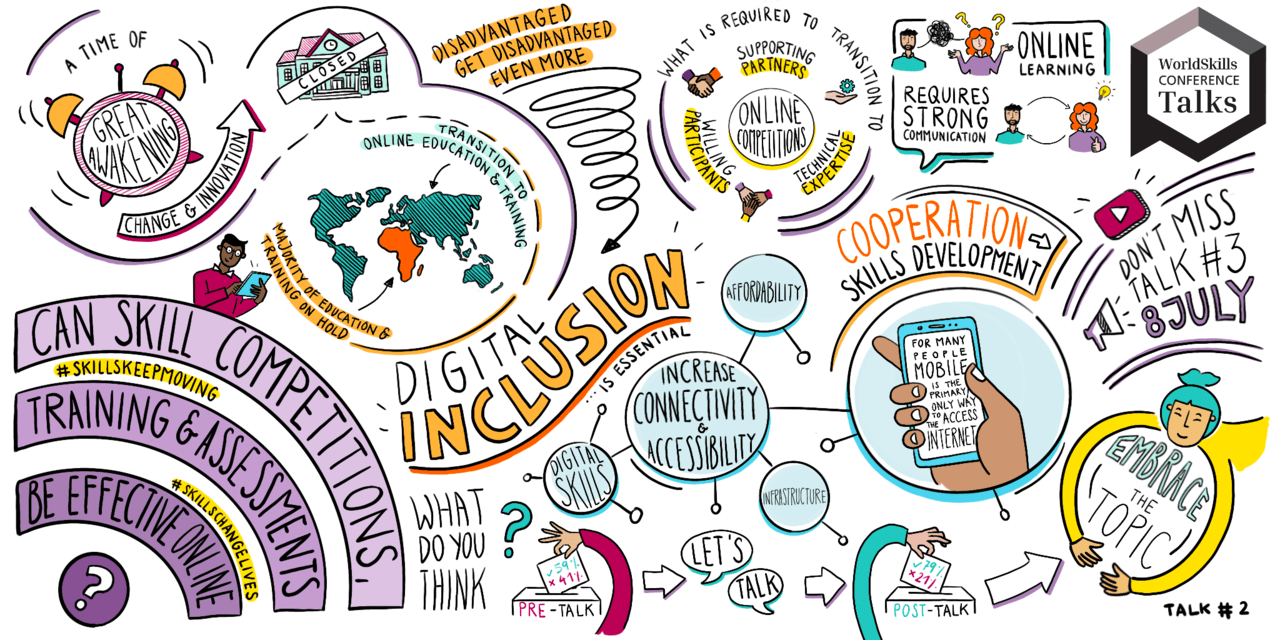

Can skill competitions, training, and assessments be effective online?

It is possibly the greatest challenge ever for technical and vocational education. How do you teach and assess young people when all schools and colleges are closed?

That was the dilemma posed by the second WorldSkills Conference Talk - itself taking place online - and essential viewing for anyone wanting to learn more about how the international skills community is moving forward.

Moderated by Ekaterina Loshkareva of WorldSkills Russia, and the WorldSkills Board member for strategic development, participants included Member countries on the front line, one of WorldSkills longest partners, and the World Bank.

It was a “most challenging situation,” Ms Loshkareva said, but one where the WorldSkills community had decided was “not the right time to put all the activities on pause.”

A snap poll of the audience at the start of the talk revealed a glass slightly more than half full. Almost six out ten watching were optimistic about moving to online training.

At the same time, that meant that nearly 40% were not.

Those figures were reflected in the contribution of Victoria Levin, Senior Economist in the Education Global Practice and a co-Lead of the Skills Global Solutions Group at the World Bank.

Their survey, conducted with UNESCO and the International Labor Organization, showed that while in 90% of responding countries all school buildings and classrooms had been closed, many were responding to COVID-19 with initiatives like supporting the training of health workers or by manufacturing personal protective equipment.

“Early findings suggest that most countries were able to switch to some sort of remote provision of training,”she said. At the same time, some regions were doing less well.

It was “quite concerning” that in Africa most of those replying to the survey had cancelled all training because they had no online or offline option.

Yet overall, Ms Levin said, the World Bank felt “very strongly that TVET can be uniquely well positioned to develop the skills that can help countries mitigate the impact of the pandemic both in the immediate term and long term.”

Just how that might be achieved came in contributions from Canada and India.

The pandemic hit home just Canada was entering provincial, territorial, and national competition season, said Shaun Thorson, CEO of Skills/Compétence Canada.

As he pointed out “people who are interested in vocational education… really like to do things with their hands. They don't typically want to be sitting behind a desk.”

Still, competitions had taken place, not just in obvious areas such as digital skills, but also in some tradition areas like carpentry.

Solutions had included sending materials to Competitors at home, using live streaming and extending the time for completion of assignments.

One competition even arranged for medals to be delivered to the winners for an online ceremony. Canada’s experience, he said, had shown working in this way needed really strong communication and worked best in smaller groups.

“As first try we think it was a great success, but we think we can go a lot further with it,” Mr Thorson said. One positive result of going online was that it offered the potential of engaging with a larger number of Competitors than the traditional classroom.

This idea was developed further by Ranjan Choudhury, head of WorldSkills India, who said the challenge of moving to a virtual platform was “what is keeping me awake at night.”

India’s initial strategy was keep Competitors engaged and aware with a social media campaign that attracted 3.7 million impressions in just two months.

India had also created a webinar on Water Technology, at which the country won a Gold medal at WorldSkills Kazan 2019, that included remote training by Experts and participants able to collect a certificate of attendance or achievement at the conclusion.

Those taking part included Competitors and Experts not just from India but eight other countries. The webinar was described by Mr Choudhury as “testing the waters, to see what were the challenges of online delivery.”

It also raised a tantalizing view of the future, in terms of greater participation offered by online working. For a country the size of India, the digital environment might more effectively reach larger numbers of young people than conventional methods, he said.

India was also looking expanding the contribution of international Experts and Competitors in the future. "We feel that their presence and being part of the assessment team would add value to the rigor of the entire assessment process.”

One skill that might be expected to resist online training and assessments is welding, but as Jason Scales, the business manager for education at Lincoln Electric, explained, a blended approach could work.

COVID-19, he said was “the great awakening”. Before the pandemic, it was believed “we couldn’t transfer knowledge unless (student) were in the classroom or in the welding booth.”

In the future, he believed, apprentices could start with virtual simulations and augmented reality before finishing at a training centre.

But he admitted “What does that look like? I don’t know. I think we are learning everyday what that opportunity presents.”

And he added a word of caution. “When we talk about the art of the skill we talk really about the proficiency of that skill.

“I can teach someone how to tighten a nut on a bolt...but learning the proficiency around welding, it takes time, it takes a coach and it takes somebody with a mastering of that skill. You can't take that away.”

Join us at the next WorldSkills Conference Talk, 08 July Ensuring that skills reflect societies: Diversity and Inclusion in competitions and beyond.